Colin Jones, Paris: A History

Haussmannism and the City of Modernity

1851-89Strategies that Made Haussmannization Possible

Even before Haussmann was appointed Prefect, an imperial Commission for the Embellishment of Paris had already begun to devise plans for the renovation of the city which in many details prefigured Haussmann's programme. Interior Minister Persigny was also developing similar ideas at the same time. These precursors may have had a scintillating vision of the modern city, however, but they lacked the political, financial and administrative clout to bring that vision to life. This is what Napoleon and Haussmann were able to provide -- albeit only from 1853 onwards. The plans of renewal which Napoleon tried out when he was still only president of the Republic, for example, had failed to make much impact. Haussmann's predecessor as Prefect of the Seine, Jean-Jacques Berger, regarded Napoleon's plans as overcasted: 'I'm certainly not going to be involved,' he noted privately, in the city's financial ruin. He proved a perennial wet blanket. Napoleon's seizure of Paris by coup d'etat in December 1851, however, and then his declaration of the Empire in November 1852, swung the balance of power his way. In Haussmann , whom he put in Berger's place in June 1853, he found an energetic and committed political fixer, who was altogether more receptive to hi s ideas, and who was more than happy to strong-arm the municipal council -- whose members he personally appointed anyway -- into assenting to his master's wishes.

Haussmann's streets and boulevards displayed the same kind of insouciant authoritarianism which he showed in most of his political dealings. This 'demolition artist', as he jocularly called himself, shunned the older piecemeal methods of improvement through the alignment of existing streets, and deployed the method pioneered by Rambuteau, which consisted of driving new streets through existing neighbourhoods. It was, he opined, 'easier to cut though a pie's inside than to break into the crust'. This urban butchery was facilitated moreover by regulations introduced in 1848 and confirmed in 1852 which strengthened the hand of the Prefect in streetbuilding projects. The 1841 regulations, originally designed to facilitate railway development, and which Rambuteau had used in his urbanization project, permitted the expropriation of properties for purposes of public utility where the property was actually on the track of a new street. The 1852 decree stated that property adjacent to the street and affected by the plans should also be subject to compulsory purchase and made available for development. This allowed chaotically complicated street- and house-plans to be almost surgically replaced by rectilinear roadways. It also permitted the construction of new buildings in replacement of what was torn down. Characteristically, the operations became self-financing, for the usually insanitary old buildings were sold at low cost to urban developers who replaced them with attractive prestige properties which could be sold or else rented ou r as homes and businesses. This allowed the accumulation of capital, which could be invested in further speculative building, a tendency which was also favoured by the emergence of a modern banking sector in these years.

For those involved in this whirligig of property development, Haussmann appeared to have invented a kind of virtuous circle which conjoined private and public energies in a way which built new homes, provided mass employment (one-fifth of the Parisian workforce was in the construction trades at the height of Haussmann's development), made a signal contribution to public health, beautified the city and supplied the financial bourgeoisie with fat profits to boot. The notion of the 'highest calling' which Napoleon and Haussmann had for a modernized Paris was, moreover, grounded in an optimistic calculus which assumed that urban growth would be self-financing in the long term. Many financial pessimists -- such as ex-Prefect Berger - argued that the city simply could not afford the scale of new building which Haussmann wanted. Yet this was steady-state financing. Haussmann built into his calculations the assumption that 'productive expenditure' -- in effect, debit financing -- would make the city bigger, richer and more attractive. By developing Paris as a world city whose inhabitants had more in their pockets, and which tourists would want to visit in droves, it would be all the easier to siphon off part of this surplus wealth, notably in the form of indirect taxes on consumption (the major item in the city's budget). This developmental logic meant that the government renovated Paris on the cheap, comparatively speaking: the state treasury bore only around 10 per cent of the total costs of the public works undertaken in these two decades. Virtually all the rest of the money came from loans, permission for which Haussmann was able to force through the municipal authorities by a combination of bullying, finagling and optimistic accounting.

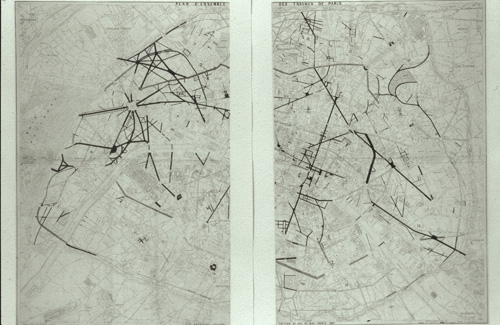

Haussmann's Map of the Streets to be Added to Paris

Photograph of Haussmann